Madlib and the Art of Jazz Excavation

The rap producer has taught me a lot about how to curate Black classical music.

Many people assume I’ve been listening to jazz much of my life. It’s likely due to the amount of jazz I write about and curate for live shows, and how much of it I play in public (on the rare times that I DJ). But I didn’t get into the genre until my early 20s, and even then, I only knew the cornerstone albums: Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew, John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme, Herbie Hancock’s Head Hunters. While those are great LPs, they weren’t the only ones breaking ground. On indie labels like Strata-East, Tribe, Flying Dutchman and India Navigation, scores of artists not named Miles, ‘Trane or Herbie were blending jazz with funk and West African rhythm, leaning into themes of Black togetherness that illuminated the music. While I could hear aggression happening within it, I could also hear pronounced joy. Surely there was anger due to the stress of racial and socioeconomic inequality, but I could also hear the love of community; the art felt like a rally to unite against systemic oppression. Across the spectrum of jazz in the late ‘60s, there were players like Pharoah Sanders and Albert Ayler, and groups like Ensemble Al-Salaam and New York Art Quartet taking the music to unforeseen places.

So, a little secret: My love of jazz didn’t come from family, it came from Madlib, the Oxnard, Calif.-born producer whose mix of muffled drums, pronounced bass and obscure samples elicits a woozy, psychedelic sound. Though technically a rap producer, his music evokes a certain nostalgia: Blaxploitation films, dusty old records, and thick smoke wafting through subterranean nightclubs. More than other producers, he leans into the dirt and revels in the mistakes. Maybe the drums drift to the left channel or the sample has a vinyl pop in it. He keeps these mishaps in the finished product, giving his music remarkable texture. Even as Freddie Gibbs raps about drugs and Georgia Anne Muldrow disses the American food industry, Madlib’s beats thump mightily in the background. Its hybrid of funk, jazz and West Coast rap feels vintage and current at the same time, like hearing warped 45s on the Hi-Fi at max volume.

Madlib is a tireless worker who, over the past 30 years, has released a stunning amount of music, some becoming cornerstones in the annals of underground rap. In recent years, his two albums with Gibbs — 2014’s Piñata and 2019’s Bandana — have given him the commercial notoriety that eluded him in the past. Gibbs, whose rhymes tend to center on the drug trade in his native Gary, Indiana, has amassed scores of fans who take to his straight-ahead takes on cocaine and the social effects stemming from its selling and usage. Meanwhile, Madlib had been a known entity in underground alternative circles; his music perhaps too weird for mainstream artists not named Mos Def or Erykah Badu. When paired with Gibbs’s hardscrabble rhymes, Madlib’s beats feel equally curtailed and prominent, giving the rapper adequate room to shine without the producer dimming his own light. With all the noise clattering throughout the instrumental, it’s easy to get drowned out by its blaring horns and vocal loops. At their best, Madlib’s beats feel like funk-jazz ensembles working out avant-garde material after the late show concludes, and they can intimidate those who aren’t equally daring.

Where jazz dots the horizon of his rap-centered work, I’ve always appreciated when Madlib went full-on jazz through the fictional group Yesterdays New Quintet and its made-up characters: Malik Flavors, Joe McDuphrey, Monk Hughes and Ahmad Miller. He creates different sounds for each: Where Malik is a vehicle for Madlib’s cosmic jazz excursions, Ahmad imparts heavy Latin grooves with polyrhythmic drums. Joe evokes Herbie’s early ‘70s electronic jazz-funk fusion, and Monk — through the album A Tribute To Brother Weldon — mixes drum-heavy backing tracks with willowy piano chords and faint synths — a slight recreation of what Wel crafted himself.

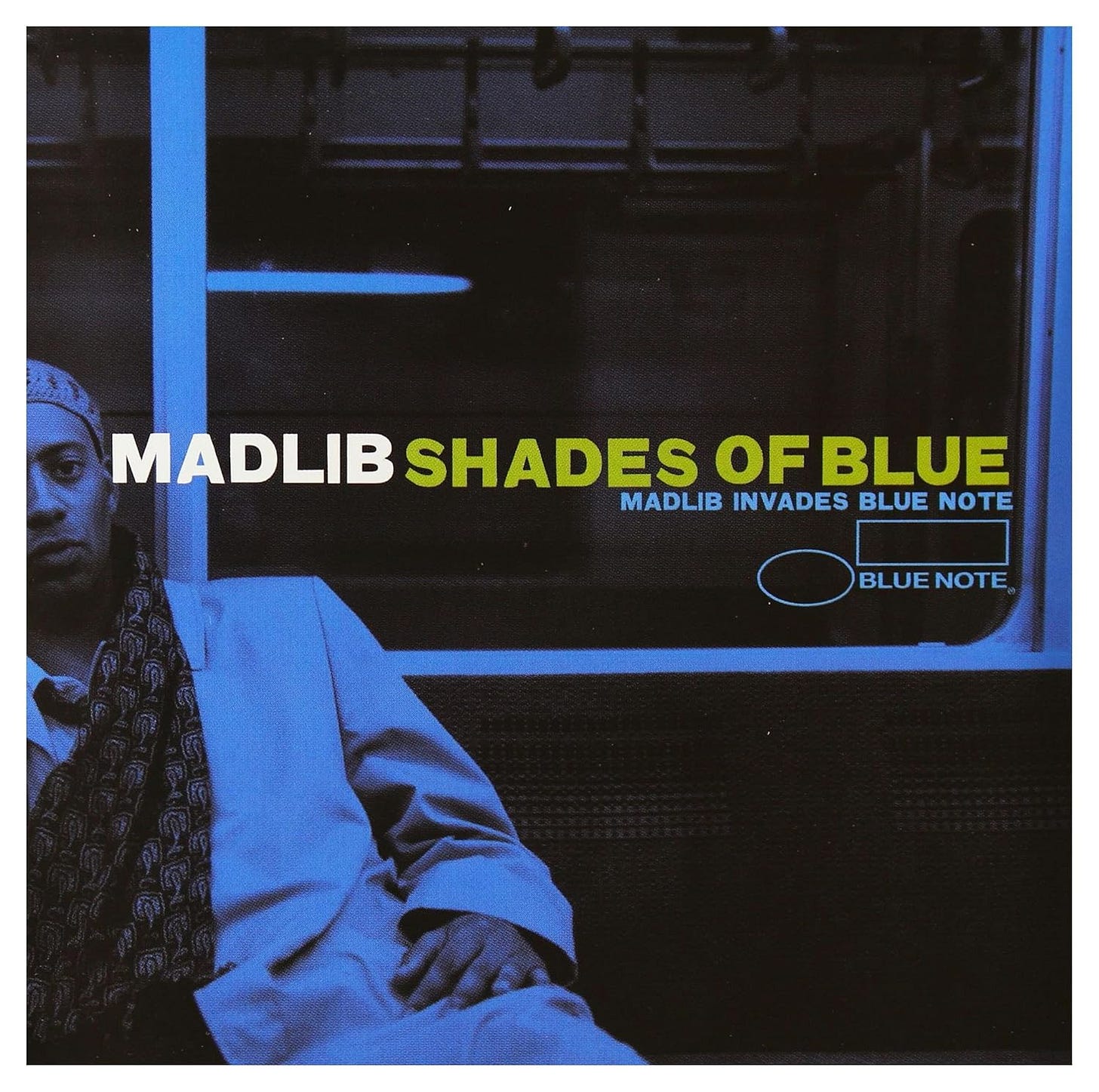

In 2003, Madlib released Shades of Blue, a remix album featuring flips of classic Blue Note tracks like “Stepping Into Tomorrow,” “Song For My Father” and “Mystic Bounce.” With its fresh spin on the cornerstone catalog, Shades of Blue introduced scores of rap listeners to classic records that maybe only their parents and grandparents knew about. It’s “the album I’m most proud of actually out of everything,” Madlib once told Spin. By replacing softer drums with harder ones, and putting rapper MF DOOM on an interlude (the two would go on to release the immensely popular Madvilliany in 2004), Madlib bridged the gap between so-called “real hip-hop” heads and jazz listeners who maybe wouldn’t give each other’s music a chance.

And where A Tribe Called Quest sampled more straight-ahead jazz from bigger labels, Madlib tapped into a fusion-based mix, appealing to those who liked unconventional sound. He was putting out jazz long before the genre had its resurgence in 2015 when, following the release and critical acclaim of Kamasi Washington’s triple album The Epic, the genre was considered “back” in the mainstream marketplace. Yet for those who listened to artists like Charles Tolliver, Jeanne Lee and Linda Sharrock, Madlib was the North Star. To a certain type of jazz head, he excavated the art we wanted to hear, and cultivated a generation of listeners who’d rather listen to albums like Kuumba-Toudie Heath’s Kawaida or Harry Whitaker’s Black Renaissance. Madlib opened the door for this type of jazz to be appreciated beyond the sample.

To my ear, Madlib’s Advanced Jazz album is the high-water mark of his jazz period. The eighth release in his Medicine Show series, it funneled a vast assortment of abstract jazz and vocal clips into a quick-moving 80-minute collage of deep cuts from lesser-known names in the genre: the pianists Horace Tapscott and Carlo Uboldi, the Afrocentric outfit JuJu, and the singer Doug Hammond, among others. Much like Shades of Blue, Advanced Jazz showcased Madlib’s experimental side, and displayed his love of overtly Black music. But where Shades felt somewhat synthesized, Advanced Jazz was uninhibited, an all-out “everything goes” collection of gorgeous melodies, face-crunching funk and comedic anecdotes, complete with weed tributes, movie trailers and repurposed interviews with jazz royalty. Presented as a 10-track, 80-minute project, Madlib stuffed the tunes with snippets of various cuts, prioritizing B-sides over well-worn classics.

Though presented as a jazz mixtape, it comes off like an ode to music overall — a walk through the archives of sound with the industry’s most fervent archeologist. There’s a palpable love radiating from this project, a sense that Madlib compiled this for himself and no one else. That’s always the best way to approach anything creative: Just do it for you and let the world catch up. Advanced Jazz introduced me to so much: It was my gateway to acts like Leon Thomas, Amiri Baraka and Billy Higgins, records that dot my ever-growing vinyl collection today. Indirectly, through this project and his other like-minded albums, Madlib taught me there’s a world beyond the usual names, and that they should be celebrated equally. So when I cover what I cover, and listen to what I listen to, it all goes back to Madlib. Full stop.

That Black Liberation Jazz and Soul comp I released in 2020?

Madlib again.

Listen to Advanced Jazz, then this, and you hear direct influences. His approach to cratedigging has helped govern my musical taste and should be celebrated accordingly.

Love Madlib and hope everyone supports him as he rebuilds. 💜

Great piece! Love to see Lib get some much deserved appreciation for his music, of course, but also for his work in bridging generational divided that sometimes hamstrings the culture.